I keep thinking of things I need to write about, since the whole ‘mom’ episode has begun to settle into dust – pardon my pun. About the process of planning burials (fire!), about how odd it must be to work in that industry. About reading a certificate that describes the end of a loved one’s […]

I keep thinking of things I need to write about, since the whole ‘mom’ episode has begun to settle into dust – pardon my pun.

About the process of planning burials (fire!), about how odd it must be to work in that industry. About reading a certificate that describes the end of a loved one’s life in stark black ink on paper that looks like money.

About what it’s like to walk into someone’s home, when they’re gone, truly gone.

It’s been difficult to find time. With typically brutal timing, my employer has decided that upcoming holidays means it’s time to kick into high gear, so I’m suddenly swamped with work again. And of course the logistics of death consumes so much time that it’s hard to actually just think about what it all means.

Last weekend, we (me, barb, my cousins sam and amy, kenny and sabine) gathered at my mother’s house to begin the process of dealing with the physical remnants of a life.

I’ve been lucky; my friend Kenny and I made a deal. He’s back from his tour, and needed a place to live, and I needed help dealing with mom’s house. So he and his lady Sabiné have moved in. They’ve done a lot of the cleaning I wasn’t ready to do, and more importantly, they make the house still feel like home. People I love still live there, and when I walk into mom’s little living room, it’s not grim, dusty and depressing, but instead warm, clean, and melancholy.

My mother wasn’t a pack rat. She was fiercely, obsessively organized. This makes my task very much easier than it might have been. Yet, in eighty years of life, one accumulates things. I’ve found a packet of confederate money, a WWI german iron cross, the official seal of the school we we helped build in the early seventies (Daybreak Institute). I found my father’s wedding ring, a strange assortment of my father’s key rings and pocket knives, a beautiful silver money clip. I found notebooks of my mother’s poetry and notebooks of my father’s sketches. I found sheet music to ‘the pink pather’, which I asked Kenny to learn for me so he can play it on his sax.

I found an entire photo album of my gramma Cookie’s that reads like an eighteen year old’s facebook page; there’s a short story to be found in it, as soon as I have time to read all the notes and copy all the pictures. My grandfather was a handsome, dashing womanizer, and it’s clear gramma had set her sights on him but not yet made him hers.

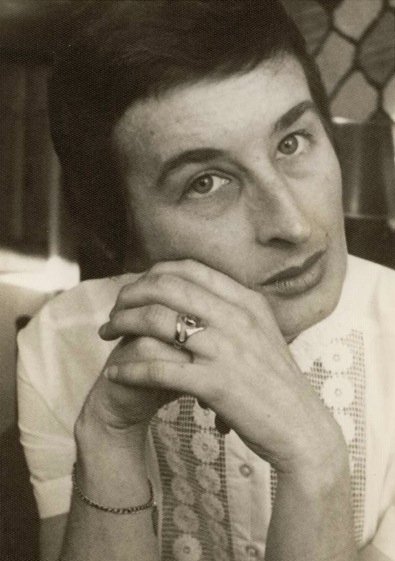

I found pictures of myself, my brother; my mother in a vietnam era army field jacket that was mine in 1972, then hers in the eighties, and and now my daughter Ruby’s.

I found pictures of my aunt Penny, and pictures of myself and Sam; we looked at pictures of our weird shared childhoods and both remembered being there, so many years ago. It’s been a long, long time since she and I have talked about being kids. I think we’d both forgotten; no one else really remembers, now. Her younger sister amy, maybe a bit, but amy’s an elemental sort who lives entirely in the now, and of course her mom and mine, my father and brother, are all gone.

The process is far from done. Yet it helps to internalize what’s happened. Seeing my mother’s bedroom empty, working through things about which she always told me “take care of this when I go”. Looking at belongings of my mother’s and father’s, here now in my home, my things. It helps. Yet I still think it every day, say it out loud to myself; “she’s gone.”

It has helped a great deal to share this with Sam. We met a few nights ago at a bar in los gatos; ostensibly because I wanted to give her my mother’s wedding ring, but I think more because both of us needed to keep taking about it all. Sam told Olivia stories about her mother, and about my mother and father. She told stories about me as a child that made my face go red. She described my parents through her mom’s eyes, as ‘beatnik poets and artists’.

It wasn’t a childhood like our children have. She grew up like a gypsy, never the same place for more than a year or so. My family were the anchors for hers; the place they could always come back to, when blood family wasn’t as close. My parents were the hard drinking, pot smoking intellectuals to her Penny’s wild child hippy, part parents, part siblings.

Seeing my daughter’s reaction to it, telling stories about a childhood that was far more unique than I tend to realize, helped me put it all in context. My relationship with my mother, with Sam’s mother, our entire family history helped me get my head around the loss of our final parent.

This weekend, I bring in a dumpster to get rid of some very old, very dusty furniture, and cart away the one or two items I’m keeping. But knowing Kenny’s there in the house, and knowing Sam and Amy remember what it was like growing up as we did, helps me not feel alone in this process. There’s continuity, from family to friends, and the house is very much a living place, with music and laughter. Someone’s reading my mother’s books, looking at my father’s paintings, and feeding the birds and squirrels that were mom’s best company the final three years of her life.

Loved ones who are still here are the most valuable thing I can think of; and I need to be sure I tell them this.